A HARD DAY’S WORK

His work on the dockside is exhausting, especially now he’s not a young man anymore. He’s glad of it though, and will take whatever he can get. Some of his pals are getting past it now, their bodies ruined by the many years of hard toil, or debilitated by injuries acquired during the course of their work.

Many a day he’s stood at those gates at calling on time and been passed over by the foreman- they take the young ones first, those who are physically strongest. He wishes they would consider the experience the older men can bring to the job. Sometimes there’s a terrible scramble when the foreman appears. He finds it demeaning, grown men reduced to pushing and shoving each other to get their hands on the metal ticket that will secure them employment for a day. It can be brutal, and the desperation palpable.

It’s casual labour, you’re taken on to get a specific job done, then paid off once it’s complete, or can be finished by fewer hands. The wages are low too. It means he doesn’t have a regular income and there’s constant uncertainty about how much he’ll make. The consequence is that the rest of his family have to go out and work to supplement his income. It’s a source of shame for him, that he can’t provide for them all. But then, there’s few other options out there and most of the families he knows are in the same position.

THE DEMON DRINK

Those are the worst days, when he doesn’t manage to get a place. On those days he’s embarrassed to go home to Heather and tell her he’s nothing to contribute, instead he’ll usually drift into one of the pubs along his route home. He tends to drink in the Irish pubs, amongst his own people. He feels most comfortable with them, they’ve been through the same hardships, they’ve also had to leave their home and family long behind them.

DREAMS OF HOME

He often reminisces about his childhood in the countryside, such a contrast to the noise and relentlessness of the Quayside- the endless shouting, the crashes and bangs of crates being lifted, the pressure to get ships loaded and unloaded, to keep the flow of goods on the river Clyde moving. He wonders sometimes what his life would have been like had he been able to remain in his native Ireland. It’s easy to romanticise the past though, especially when the present is so fraught with risk and uncertainty.

A BETTER LIFE

He hopes things might be a bit easier for his children, less of a struggle. He knows Heather misses Lizzie something terrible, but she’s doing well over in the West End. He feels like his eldest son Edward looks down on him sometimes, he makes him feel a bit inadequate. Edward’s smart, and his fastidiousness will ensure he never knows hard labour. He’s got himself involved with the temperance movement, and he lectures his father sometimes about the trouble with drink and the problems it causes. He knows deep down that he’s probably right, and he tries to go a bit easier on the drink these days under Edward’s influence. It’s not easy though, drink’s his escape from reality and the trauma of his past. Then there’s wee George, who always makes him feel positive. He’s always up to something, coming up with this scheme and that. He’s got entrepreneurial spirit alright, he’ll definitely land on his feet…

OUR INSPIRATION

THE GREAT FAMINE

Also known as the Famine, the Great Hunger or the Irish Potato Famine, The Great Famine was a period of mass starvation and disease in Ireland which lasted from 1845-52. Estimates vary, but during that time around a million people perished and another million left their homeland. By 1855 the number who had emigrated had reached 2 million. Often it was the younger and more capable members of the family who emigrated first. Unlike similar previous emigrations, women left as often and as early as men. The expectation was they would secure work and be able to send money home to the rest of the family. Thomas would have been in his early twenties when he left Ireland for Scotland.

Emigration during the famine years was primarily to North America, but for those who couldn’t afford to cross the Atlantic, Scotland was the nearest port of call. Even that journey could be perilous, with overcrowding and poor conditions onboard boats that were not fit for purpose. Many, already substantially weakened by the Famine, did not survive the journey. Due to their poverty and often poor state of health, Irish immigrants tended to settle near their point of disembarkation, which in Scotland meant the west coast.

THE GLASGOW IRISH

Glasgow’s industry was a pull for immigrants as it provided a range of employment opportunities.

Irish men tended to settle in jobs that required strength, such as dock work. It’s been estimated that in Great Britain in 1851 somewhere between a half to three-quarters of all dock-labourers were Irish (www.sath.org.uk). Many Irish women worked in the textile industry or in domestic service.

The Catholic Irish tended to keep themselves to themselves, creating their own community with strong ties and setting up their own churches and schools. The Church was a focal point in their lives and provided a range of social and recreational opportunities. In 1887 Celtic Football Club was founded in a church hall in the Calton by Brother Walfrid, an Irish Marist Brother. The purpose was to alleviate poverty in the immigrant Irish population in the East End of the city by raising money for a charity Brother Walfrid had set up, the Poor Children’s Dinner Table. Establishing the club as a means of fundraising was inspired by the example of Hibernian, which was formed out of the immigrant Irish population a few years earlier in Edinburgh.

A new memorial to those who died in the Famine was unveiled outside St Mary’s Roman Catholic Church in the Calton in July 2021, the very same church where Celtic was founded.

WANT TO KNOW MORE?

-

Read Irish: The Remarkable Saga of a Nation and a City by John Burrowes.

-

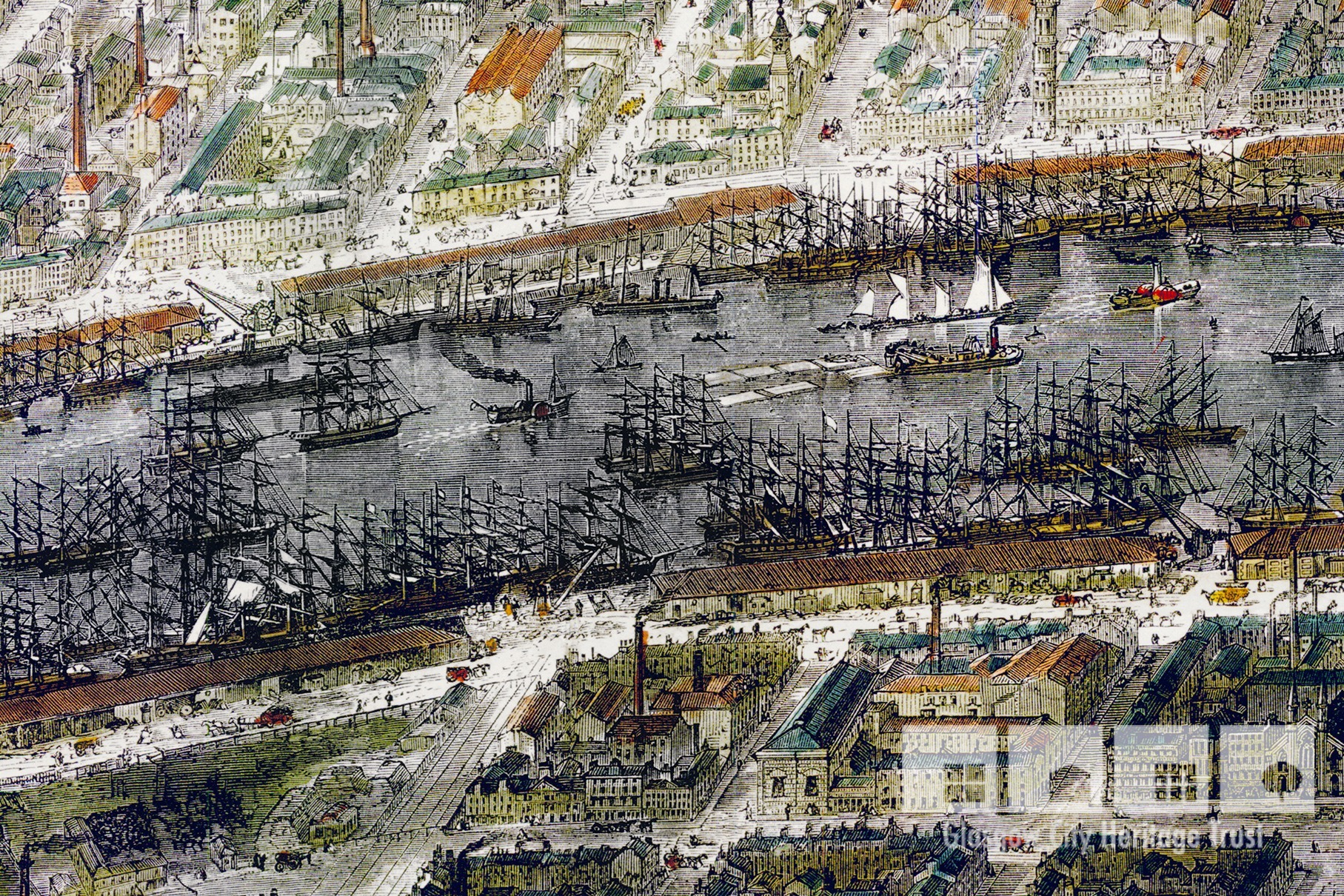

Explore Sulman’s map here. Zoom in to see the amazing detail along the river Clyde and get a sense of how busy it was.

-

Head over to our online shop where you’ll find prints of Sulman’s map, including the Tradeston and High Street areas. Every purchase supports our work!