For this month’s Blog, we’re talking to Building Conservator & Educator, Darren McLean, for some insight into why many of the Glasgow Ghost Signs have survived for so long.

J: Can you give us an introduction to yourself and the work you do Darren?

D: Well, I’ve a passion for historic buildings and I’m fortunate enough to make a living not only by hands-on conservation, but teaching it too. I spent considerable time in Italy, where I studied traditional Marmorino marble based plastering in Venice, as well as the conservation of mosaics in Ravenna. In 2018, I became an adjunct assistant professor at The University of Hong Kong, responsible for the materials and techniques modules of the postgraduate conservation curriculum. I’ve also taught for heritage organisations, such as Historic Scotland, Glasgow City Heritage Trust, National Trust Australia, and the Yangon City Heritage Trust. I mostly work with wood, masonry, lime mortars, natural cements, mosaics and tile. I’ve also (very relevant to this topic) recreated and tested various historic whitewash, paint and varnish recipes.

J: You have a great understanding of the materials and techniques used in historic buildings, but you also know what went into the creation of many of the Ghost Signs we find around Glasgow that have helped to preserve them so well.

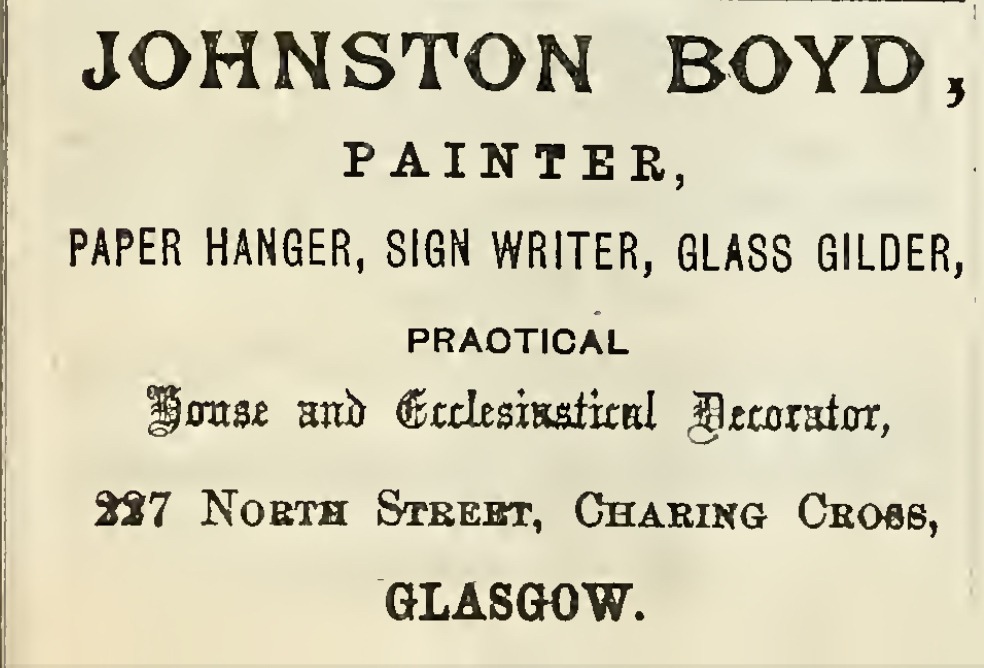

D: Sure, and a good place to start is to clarify the different types of ghost signs we find today. In general, signs that involve paint were applied on wood, masonry and occasionally onto glass – something you tend to see more often on the continent. The science of making durable paints for all these substrates was well known centuries ago. It was routine for painters to produce their own paints, prior to the advent of ‘off the shelf’ tinned paint, and even then, they often needed to be manually tinted. Books relating to the architectural trades rapidly spread information & instructions on the production of materials, including recipes for paint. Many books offered advice on durable paints for signage, as well as which paints to avoid that were not so long lasting. Something very important when painting a difficult to access tenement gable!

To look at signage on masonry, large wall signs were first drawn on paper, then the ground (base) was applied to the masonry wall and chalk lines used to create guide lines for the letters. Often these were drawn with broken clay pipe stems, sold for this purpose direct from factories such as the one located at the Barras. The best way to make painted signage last was to have a stable and durable base, often a type of whitewash (the name for limewash until the early half of the 20th century). Various additives improved adhesion and durability. Oil based paints (typically Linseed oil) created a durable ground, with linseed often added to whitewash to improve its adherence and resistance to erosion. Whitewash was always applied hot in the past, which vastly improved its ability to bond with its substrate. Whitewash is one of the cheapest types of ‘paint’ available, even today. This cost advantage was very important, as advertisers weren’t only painting shopfronts and building gables, they even painted enormous advertisements onto seaside cliffs – not a feasible option with expensive paints.

When painting shopfront glass, paint was applied to the inside, although not exposed to wind and rain, this could suffer from exposure to UV light. Nowadays synthetic pigments are often used to withstand UV light, however the pigments used in the past were predominantly natural, and derived from earth minerals which were UV resistant and colourfast: Ochre, umbra, sienna, burnt sienna are all extracted from various clays. While lamp black – a deep black pigment – is made by burning vegetable waste. Signage painted onto wooden shopfronts used oil paints, and occasionally gilding, then were protected by varnish. These were frequently installed at an angle, so the top of the sign is proud of the base. This created a slightly sheltered situation for the writing and, in some situations, there is a stone course, which is part of the building, directly above the timber. Both these provided protection for the paintwork, meaning that they are amongst the most frequently seen types of ghost sign.

Unfortunately, paints could include some nasty stuff, such as lead, which most everyone will know is toxic. But there was worse: a wonderfully deep vermillion red was obtained from mercury sulphide-rich cinnabar, antimony and arsenic for yellows. Antimony was helpful as it slowed the drying of paints. Even reasonably safe products, manganese for instance, became toxic to those manufacturing the paints, due to the frequency and duration of contact, and inhaling dust.

J: Given that some of the additives used in sign painting could be toxic, were they also harmful to the fabric of the building?

D: Not really, where the masonry of buildings has been painted for advertising, it tends to be up high for visibility and doesn’t have the same deleterious ‘clingfilm’ effect as painting the entire building. It’s somewhat counter-intuitive, but high up walls will get wet, but also dry out faster as there’s more wind to assist evaporation. Even where ghost signs appear near ground level, such as the Regalia Whisky ghost sign in Partick, they don’t cause the kind of harm modern masonry paint does, the old paint was different & often weathered back, allowing evaporation to occur.

J: Are there less toxic materials around today that could produce the kind of longevity that the old methods produced?

There are, of course, highly durable, modern specialist paints available nowadays – think of paint used for airplanes, ships & oil rigs. But there are also durable water-based paints, that are far less toxic than historic paints. If someone were to repair or repaint a sign and permeability was a concern, I would recommend silicate paints which, although expensive, are available in a wide range of colours and have been in use since the late 1800s. They may not be as permeable as whitewash, but are far superior to plastic paints and very long lasting when applied correctly.

J: Heated debate has arisen around conservation of Ghost Signs. During our Conference on Ghost Signs last year, we held a panel discussion on their preservation, bringing together Ghost Sign sites from across the UK & Ireland. Whilst our combined efforts do much to document & archive these ephemeral works, there were mixed views on conservation. Can you offer a view on the various approaches such as protecting with some form of coating, reviving through repainting, or leaving them to fade?

D: “Heated” is right, you could say that about almost every aspect of building conservation! Ask three conservators this question and you’ll get three (or more!) replies. The protective coatings option, can be a double-bladed sword. Few are as breathable, or permeable, as portrayed. With consequent dangers of moisture building up behind them and creating a blister effect, pushing the surface of the masonry away. Personally, I don’t like the idea of allowing things from the past to vanish, where it’s feasible for them to be sympathetically and respectfully kept for future generations to appreciate, or learn from. This may involve cleaning, or sympathetic painting to keep its present state. Having said that, bringing these things back to their original vibrant colours is too far the other way for me. It risks misinterpretation through conjecture. I like the Italian attitude, where what’s visible is conserved as sensitively as prevailing conservation practices allow, and where there are missing areas of a wall painting or mosaic, modern materials are used to recreate the missing section. This has no impact on the nearby original historic fabric, yet tells a story, educates and, should more information become available, is easily removed or modified.

J: There seems to be a lack of regulation to protect this relatively new aspect of our built heritage. Some host buildings for ghost signs have listed status, such as the St Andrew’s Print Works building on Pollokshaws Road, but what’s your view on a legal framework that ensures ghost signs are considered on planning applications?

D: For me, retention of a building’s historic fabric is at the heart of conservation. The majority of historic buildings in Glasgow are residential properties in private ownership. A considerable number are in conservation areas or listed. If listed, it’s because the building is linked to a historical significance, be that something famous – or infamous – political, religious, artistic, or scientific. So listing is really an acknowledgement of historical events. Where a ghost sign has survived, and is visible, it IS a piece of history. Indeed, ironically, the signs can be more honest than the buildings themselves, which may have had numerous alterations over the decades, many of which are not obvious.

A commonly used term in conservation refers to the “Character defining elements” of a building’s physical attributes. These can be carved stone facades, ornate plaster ceilings or something much more ordinary. The things that make a certain building interesting, if not unique. What can be more character defining than a massive painting on the side, or a subtler one painted on glass? A sign which reflects the lives of people around the time they were painted & that became a reference point for generations of local people!