By Caroline Bressey

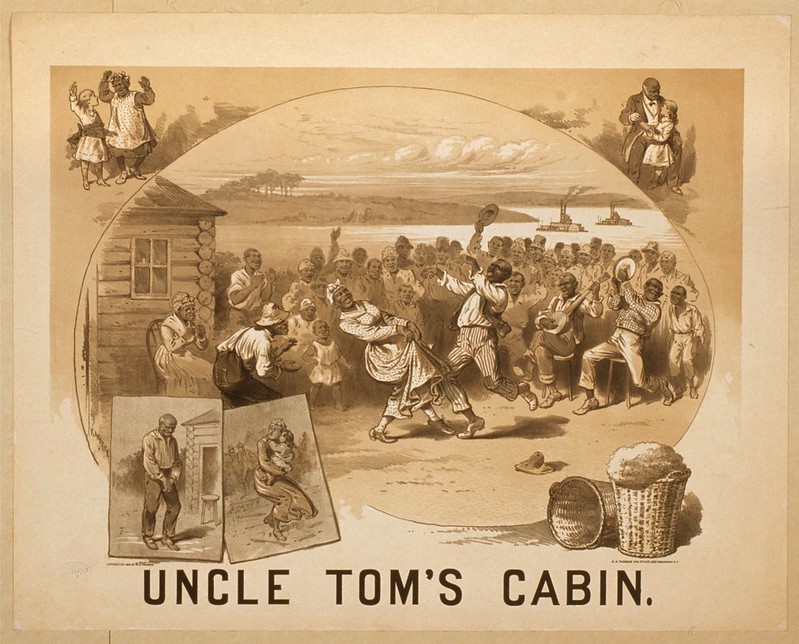

AN UNPRECEDENTED SUCCESS

On Thursday 26 February 1880 an advert was placed to catch the attention of readers of Glasgow’s Evening Citizen. Carried among the ads for ‘amusements’ that could be enjoyed that week was one for Uncle Tom’s Cabin, then showing at the Prince of Wales Theatre. The show was being met with ‘thunders of applause’ every night, and consisted of a ‘magnificent dramatic company’ which included American comedians, ‘original jubilee singers’ (a choir of African American singers) and ‘freed slaves’. It was claimed to be an unprecedented success in the history of drama in Glasgow. The theatre promised that overflow tickets issued on a Saturday evening when some hundreds were unable to get in would be available any evening during the show’s run. The following week, perhaps to ensure that potential audience members were aware of the authenticity of the cast, another ad carried the additional tag that the cast included ‘real negroes’.

‘TOO WELL KNOWN TO DEMAND COMMENT’

Readers of the Citizen would likely have known well the story of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, though it had been published almost 30 years earlier. When an 1872 production opened in Glasgow, the story was deemed ‘too well known to demand comment.’ Published by Harriet Beecher Stowe in Boston in 1852, the book became one of the most important and best-selling novels of the nineteenth century. When it was printed in London in 1852, it was given a slightly different title: Uncle Tom’s Cabin; or Negro Life in the Slave States of America, making clear its central concern with the lives of enslaved African Americans.

The book was a sensation in Britain and was read and performed in many different settings. In February 1857 the Glasgow Courier carried an announcement that for 3s a ticket, audiences would be able to hear Mrs Webb, ‘a coloured American Lady’, reading from Uncle Tom’s Cabin at the McLellan Rooms that Friday evening. Given the immense popularity and success of the novel, it is not surprising theatre producers sought to capitalise on interest in the story, and versions of Uncle Tom’s Cabin remained popular on theatre programmes in Britain for the remainder of the century.

The first stage productions opened in the United States in August 1852, but Britain was not far behind with adaptations at the Standard and Olympic Theatres in London and the Theatre Royal in Edinburgh all opening in September. It’s likely the first stage version in Glasgow was produced not long afterwards. Certainly by February 1853 the Theatre Royal, then on Dunlop Street, was boasting in an advert placed in the Glasgow Free Press, that a crowded house watched their version of the show every night. Its popularity was such that Uncle Tom’s Cabin was programmed to be performed every night until further notice.

SPECTACULAR THEATRICAL VERSIONS

The 1870s saw one of the most spectacular theatrical versions created by the American producers Jarrett and Palmer. In 1878 they announced a new kind of staging of the novel which would involve a vast cast including over 50 Black actors. Though the entire version of this American staging did not perform in Glasgow, a chorus of Jubilee singers joined a production which played to crowded and enthusiastic audiences at the Prince of Wales theatre. A February 1879 review in the North British Daily Mail (Scotland’s first daily newspaper) commended all aspects of the work particularly the ‘singing and dancing of the bona fide Jubilee Singers’ who the reviewer felt, invested the play ‘with a realism totally beyond ordinary expectations.’

The reviewer’s highlighting of the Jubilee singers’ authenticity illustrates the complex relationship Black performers and hopeful actors surely had with the staging of the novel. The play offered important roles in the careers of actresses who found strong and serious roles adapted from white characters in the novel. With Black women also key characters in the novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin could provide stage roles for Black women, but often white actresses and actors took all the main parts. In some productions Black actresses could find parts playing more minor roles, and in time Uncle Tom himself would be played by Black actors.

OTHER ROLES FOR BLACK PERFORMERS

Enduring productions throughout the 1880s and 1890s generated ongoing advertisements for ‘Coloured people’ and ‘Jubilee singers’ to join shows across the country, but though Uncle Tom’s Cabin provided roles for Black performers they were undoubtedly being asked to perform very particular ideas of Blackness in these plays. Yet, these weren’t the only parts available for Black people seeking to make a living upon the stage. The African American performer Amy Height did take on parts in Uncle Tom’s Cabin in England, but she also performed at the Gaiety Theatre on Sauchiehall Street in December 1892, when she was billed as a ‘Coloured American Songstress’. Known as a comedian and soprano, she also performed as a ‘negro ballad singer’ at the Scotia Variety Theatre on Stockwell Street.

In September 1899, the Royal Princess Theatre in Glasgow placed an advertisement for: ‘a Coloured Lady for Comedy Part in Pantomime’. Anyone interested was to send their terms, a photo and further particulars to Mr Waldon – presumably Rich Waldon, manager of the theatre from the 1880s. Of course, the placing of an advertisement does not prove that a Black woman appeared in a pantomime at the Princess Theatre that year. The advertisement does tell us that Black performers were out there, looking for and hoping for work, travelling around the country, having their photographs taken for potential employers and sometimes treading the boards of Glasgow’s theatres. While they did so they would have become part of the city’s community of jobbing performers, entertaining audiences, and off stage sharing rooms and stories with fellow actors before moving on, or perhaps settling down. If they did stay, which parts of Victorian Glasgow they made home is still to be recovered.

Caroline Bressey is an historical and cultural geographer at University College London. Her research focuses upon the Black presence in Victorian Britain and how our histories are represented in heritage sites. Her book, Empire, Race and the politics of Anti-Caste examined a radical anti-racist reading community established by Catherine Impey in 1888.

WANT TO KNOW MORE?

- Explore our Gallus Glasgow map, featuring several theatres.

- Prints of the map are available to buy in our online shop

- The Arthur Lloyd website has comprehensive information on Glasgow’s theatres.