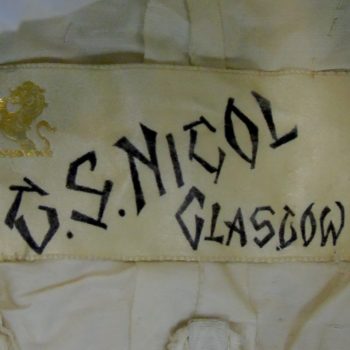

These past months have undoubtedly been very strange times to live through, but for many they have also been a time to see our city anew. The surreal photographs of familiar thoroughfares, that circulated in recent months, pictured a city completely bereft of people. The built environment was brought into focus in many ways, during these extraordinary times, from the renaming of street signs to the reclaiming of the streets for humans.

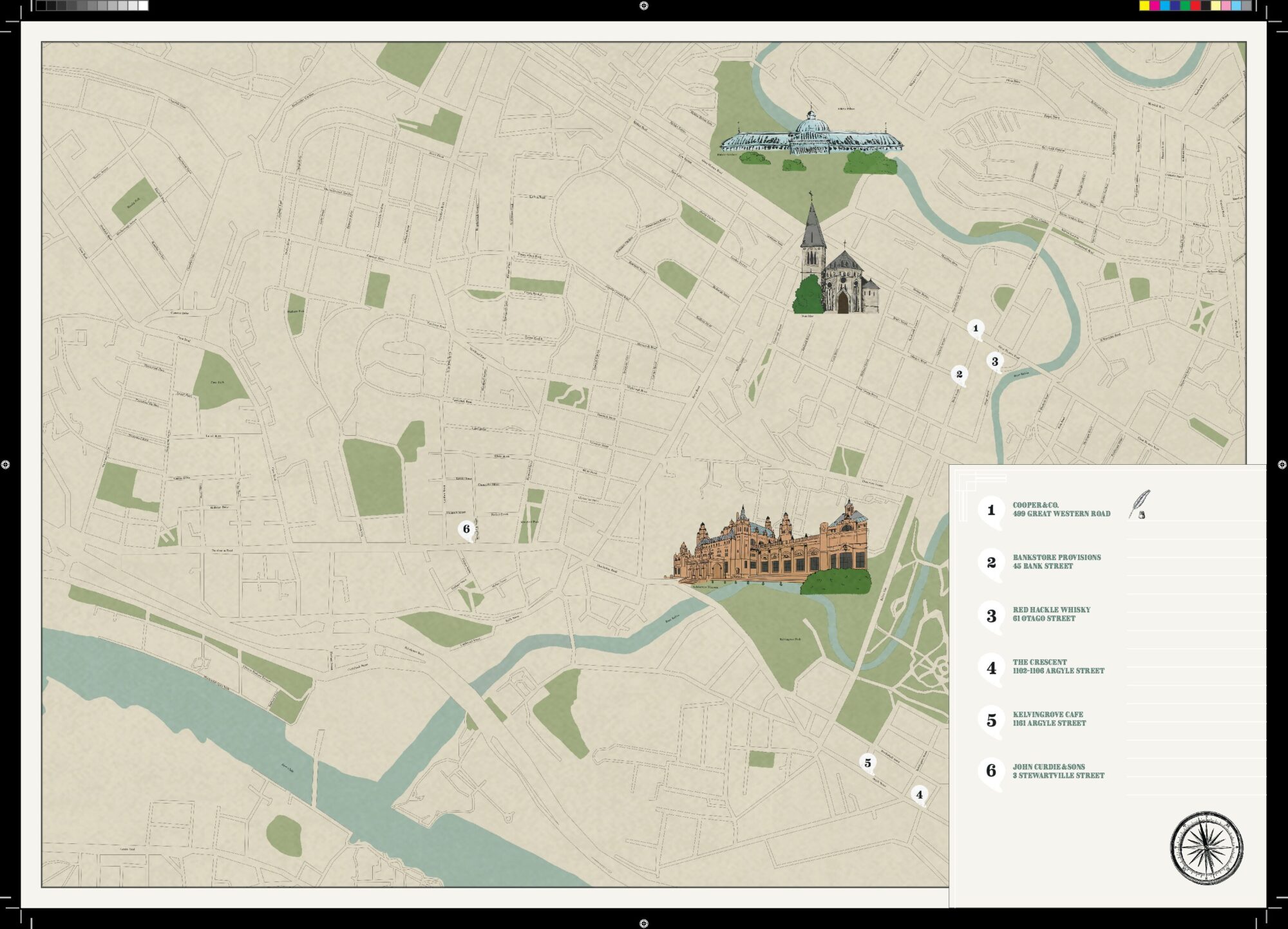

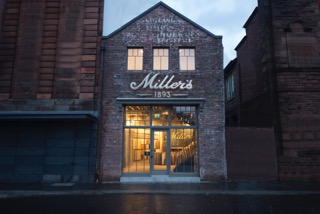

As the Ghost Signs of Glasgow project enters a new phase, under these unusual circumstances, it’s worth reflecting on the significance of the project for Glasgow’s built environment. Preserving and archiving old signs, faded to the point of illegibility, isn’t just a form of commercial archaeology, it also serves to activate the public memory and social history of the communities surrounding these sites. Because the ghost signs are not purely objects in themselves, but are situated within a wider set of historical, social and environmental contexts, they act to recover many of the Glasgow oral histories that might otherwise be lost to us. Therefore, the signs aren’t just about the remains of the commerce of Glasgow’s past, they are also about the lives of Glasgow’s people too.

This next stage of the Ghost Signs of Glasgow project will see original founder Silvia Scopa, pass the coordinator mantle onto Jan Graham and Merryn Kerrigan, two Glasgow School of Art graduates who have been with the project from its beginning as volunteers. The two plan to continue in the vein of Silvia’s work to establish the project, alongside the dedicated team of project volunteers, documenting, researching and archiving ghost signs from across Glasgow. While future plans for the project have evolved to operate within the ‘new normal’ including an online ghost signs conference with speakers from across the British Isles, virtual ghost signs city tours, and a virtual tour of the up-coming Ghost Signs of Glasgow photography exhibition. Stay tuned!